Marie Kennedy's love of music had brought her to the Stardust. She loved the Bee Gees. She loved the Jackson Five and Leo Sawyer, and she loved Abba.

She made up dance routines and taught them to her younger sisters and their friends. She showed them how to sing and perform the Hucklebuck.

Marie would hug her Mam from behind and call her by her first name, Patsy. She adored shoes and would spend her pay on them.

She would become her family's "Dancing Queen", only and forever 17, lost in the smoke and devastation.

Michael Ffrench was really into his music. He was generous with his apprentice electrician wages.

He'd put his siblings on the crossbar of his bike and cycle them to St Anne’s Park so they could play.

He would dance around the kitchen with his mother to cheer her up.

It took 25 years to identify his remains.

Mary Keegan was a beauty. She looked like Farah Fawcett Majors, right down to her hair.

Every day for months after she was killed, her three-year-old brother would sit on their front doorstep and wait for her to come home.

Michael Farrell loved music too. He loved Bruce Lee, loved dancing. He displayed his pitch and putt trophies with pride.

Before he went to the Stardust, he'd asked his sister Monica to get a Valentine’s card for him to give to his girlfriend. But the man behind the shop counter had teased Monica because the card had the word 'Girlfriend' on it.

'That’s the last Valentine's card I’m ever getting you,’ she'd told Michael.

Michael never come home.

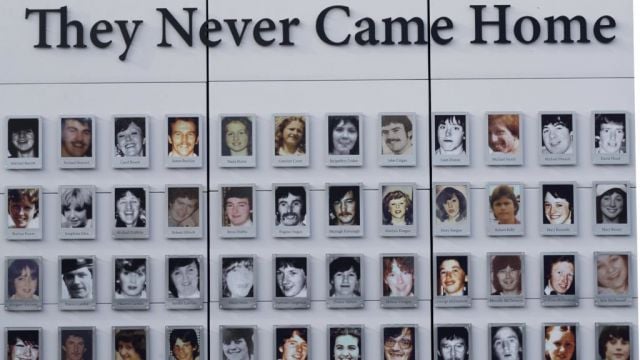

Four victims of the Stardust fire. Four out of 48.

During a Coroner's Court inquest where thousands of questions were put to hundreds of witnesses over the greater part of a year, Michael's niece Angela Shepard decided instead to ask a question of the jury: "I’d like to ask you just for a moment to imagine you never went home. What would your family’s reaction be? If they never saw you again, never spoke to you again, never held or hugged you again.

"What answers would you expect your family to get?"

In the pillared, plastered surrounds of the Rotunda Hospital, where a jury had been assembled to provide such answers as to how and why Michael and 47 other victims of the 1981 Stardust nightclub fire had died, Angela pointed to a collage of those who had their lives taken away: "All of those young, beautiful smiling people suspended in time for decades. Waiting for validation and answers, for justice and accountability."

Born to be alive

The building that housed the Stardust ballroom was constructed in the northside Dublin suburb of Artane in 1948. Owned by R&W Scott Ireland Limited, it was used for food processing and was known locally as the Scott's Foods factory. The shares in the company, which was subsequently named Scotts Foods Ltd, were ultimately acquired by members of the Butterly family.

In 1972, the owners made the decision to convert the building into an amenities centre. Between 1977 and 1978, part of the building which had been previously used for making chocolate and for storage was converted into a complex which consisted of the 'Silver Swan' bar, the 'Lantern Rooms' restaurant and the 'Stardust' ballroom. The centre opened to the public on March 6th, 1978.

Within the Stardust were a main bar and dance floor, two smaller semi-circular bars, western and northern alcoves with seating and a stage with a backstage area and other utility rooms.

There were eight exits from the Stardust part of the complex, of which six were intended to be used as a means of escape during an emergency. These six included five emergency exits and the main entrance.

These exits, entirely crucial to every form of investigation into the fire, would be referred to numerically throughout the inquest. Exit 1 opened out on to a steel fire escape descending to a concreted area. Exit 2 was the main entrance to the Stardust. Exit 3 was on the south side of the building and opened out on to a flight of five steps down to a concreted area, while Exits 4, 5 and 6 on the east side opened directly on to this area.

In February 1980, the activities in the Stardust, now one of the largest ballrooms in the country with a capacity of 1,458, were extended from cabarets and concerts to the holding of 'disco dancing' on Friday and Saturday nights.

The Stardust St Valentine's event for 1981 had drawn a large crowd of young people from the local area, with more than 800 in attendance for the disco and a dancing competition. It fell on a Friday the 13th, and the song chosen for the competitors to dance to was by Patrick Hernandez's Born to be Alive.

Excitement had built and by 11pm there was a queue to get in that stretched across the front of the building. The event was described as an 'Over 21s' disco, but the inquests heard that 83 per cent of those present on the night were under the age of 21.

The majority of witnesses who testified told of how they were not required to provide evidence of their age when entering the club. Out the 48 victims who would die in the fire that would engulf the club that night, half were aged 18 or under. Four were only 16-years-old. Caroline Carey, who was taken from the club but pronounced dead in hospital, was pregnant at the time.

Witness testimony would bring the youth of the victims starkly into focus. Survivor Patricia O’Connor told the jury how she still hears the cries of people calling for their parents as they tried to escape.

“There was just… people screaming Mammy, Daddy help me…open the doors. That’s what I heard, that’s what I still hear,” she said.

A glow

Noel Scully awoke to a noise like fireworks. It was 1.15am and, having put his head on his pillow only 15 minutes earlier, he left his bed, pulled the blinds and looked out the bedroom window of his home on Kilmore Close in Artane.

Warming the winter night, he saw a glow that looked “almost like city lights from a distance”. It was coming from the direction of the Stardust.

Concerned, he got dressed and left his house at 1.20am, driving in the direction of the club.

When he got to the Stardust, he was met with an "extremely odd" sight. A young man was walking on the footpath near the entrance of the club, his face and clothes blackened. Mr Scully said the man was walking towards Beaumont Hospital and he tried to persuade him to wait for an ambulance.

“I put my arm around him and his coat broke. He slipped down and some of his hair broke off,” Mr Scully told the inquest.

The dancing competition in the Stardust ended sometime between 1.20 and 1.30 in the early hours of Valentine's Day, with DJ Danny Hughes handing out prizes for the best performances. Errol Buckley was one of the winners and his brother Jimmy had lept onto the stage to hug him and tell him how proud he was.

Assistant DJ Colm O'Brien took over the decks, with patrons then invited to return to the dance floor. Those who did told friends that they could feel heat coming from the roof.

John Molloy told the inquest that he thought it was quite warm, but at the time “didn’t think anything of it”.

Sometime after 1.30am, Dermot O’Neill, who worked for a company booking entertainment for the nightclub, heard some girls complaining of a smell as he made his way back to the main bar.

Stardust regular Linda Bishop, who was aged 18 in 1981, told the inquest that it had been noticeably cold in the building on the night of February 13th and that she and her friends had asked the bouncers to turn the heating on.

Her night out was going as normal until she felt a blast of heat shortly after 1.30am. “I suddenly got a shudder, that’s the only way I can describe it,” she told the jury.

And when I find her, I'm gonna kill her

A few minutes later, she and her friend went back out on the floor to dance to the song 'Lorraine' by London two-tone band Bad Manners.

For Brian Baitson, 18-years-old at the time, it was his first time at the Stardust. He was also on the dance floor with his friends moving to 'Lorraine', its chorus repeating: 'And when I find her, I'm gonna kill her'.

He decided to check his watch and saw that it was 1.40am.

Sharon Hanlon had also noticed a peculiar smell. Shortly after the dancing competition ended, she sat down at a table in front of the West Alcove, where one of her friends asked if she could smell smoke. Sharon, just 17 at the time, got down on her hunkers and looked under a partition sealing off the alcove.

There, she saw that some of the seats were on fire.

Sharon told the inquest that the fire was right at the very back of the bank of seating when she saw it and had not yet spread to the wall or the ceiling. She said that a member of staff approached and lifted the shutter because someone had alerted him to the fire behind the partition.

Anthony Kavanagh gave evidence that he too noticed a fire behind the screen partition in the West Alcove and saw a member of staff approach the screen.

“I was saying to myself: ‘Please don’t open it,’ he told the jury. "I was praying that he wouldn’t open it."

But the screen was pulled back and at the moment, Anthony said, "flames shot right across the middle of the floor.

"That’s when all the screaming started."

Doomed to fail

Despite having been given "no fire training whatsoever", some members of staff immediately tried to tackle the blaze.

The efforts of Colm O’Toole, a 20-year-old barman in 1981, were acknowledged in particular at the inquest by lawyers acting on behalf of the families of the deceased.

Mr O’Toole said there was “no plan in place” when the fire broke out, with a small number of staff working to bring it under control while the music continued to play.

“It was almost like business as usual, the music was still going and people didn’t know really,” he said.

In a statement, assistant DJ Colm O'Brien said that he looked over to the area of the hall that was partitioned off and saw through the raised partition “a small fire”.

"As the fire got bigger, I could see some of the people begin to panic. I then made an announcement over the microphone," Mr O'Brien said.

Resident DJ Danny Hughes was in the Silver Swan bar having a brief conversation with manager Eamon Butterly when someone came in to say there had been a fire.

In his statement to gardaí, Mr Hughes said Mr Butterly made a comment that “they have set us on f**ing fire”.

He said he left and went around to the main entrance where he intended to tell Colm O’Brien to play some more records.

“At this stage I thought it was just people panicking unnecessarily,” he said, adding he couldn’t get in the door with the amount of people coming out.

In his direct evidence to the inquest, Mr Hughes said he thought that the people in the Stardust should be asked to evacuate the building slowly, with two or three more records played. “I thought the correct thing to do was to ask the patrons to leave in an orderly manner,” he said.

“Your concern was the possibility of panic unnecessarily rather than a concern for immediately evacuation?” Sean Guerin SC, acting for a number of victims’ families, asked him.

“My intention was to calm the situation down as best I could,” said Mr Hughes.

Mr Guerin put it to the witness that this was the wrong thing to do.

“That where there is a fire in a nightclub the only appropriate course is to arrange for the immediate - calm and un-panicked obviously - but the immediate evacuation of the building.”

Asked if he had any comment to make on that suggestion, Mr Hughes replied: “My comment is that I didn’t want 800 people rushing for the doors all at once and to collapse on top of each other.”

“It might not unreasonably be observed Mr Hughes, that no one would want them dying in a fire either inside the building and that’s why it should have been immediately evacuated,” said Mr Guerin.

I reject that suggestion,” Mr Hughes replied.

The DJ confirmed that he had never received any training in what to do in the event of an emergency.

Barman Colm O'Toole, meanwhile, was engaged in efforts to use a fire extinguisher to douse the flames that he said were "doomed to fail". “It had no effect,” he said.

In his original statement, Mr O’Toole said that when he realised the fire extinguisher was not effective, he tried to direct people out of the building through an exit in the dispense bar that many patrons would have been unaware of.

“I tried to tell the patrons that there was an exit through the dispense bar but no one seemed to hear me,” he said. The smoke was getting very dense at this stage.”

He told the inquest that after he left, somebody came out who had been overcome with smoke.

“I held them for a while,” he said. “I don’t know who that person was.”

In a matter of minutes, the fire would consume the Stardust.

Survivors told of the flames travelling across the ceiling, of burning molten material dropping from above, of the panic and confusion that set in as the lights went out and black, acrid smoke engulfed them.

Christine Carr told the jury that the fire she saw on the night of the fatal blaze was like “looking into hell”, describing a “rainbow of colours” that was “mesmerising” as the flames spread across the nightclub ceiling.

Deborah Osbourne told of how the fire was like “a monster, a living thing that was coming after you”, as she recounted how, while battling to escape, she thought she was going to die as she lay on the floor with one of the victims, Sandra Lawless.

Bernard Tully compared the fire to the movie ‘Backdraft’, describing “a big ball of flames” that went right across the ceiling, while Anthony Preston said that "people were giving up because of the fumes".

"They were dying before the fire got to them," he said.

The ferocious heat of the blaze caused the suspended ceiling to collapse. Marie Hogan and her husband Eugene had been at the Stardust to celebrate, as they and their two children were due to move to Kerry the next day to start a new life.

As the fire started to spread, Eugene told her to wait while he went to get their coats but, as he was going up the stairs, the lights went out.

Marie was pushed and carried by the crowd toward an exit, where eventually: “A young fella grabbed me by the hand and pulled me out. Somebody told me that Hughie was already out, but he wasn’t, he never got out,” she said.

“I saw the roof collapse where we had been sitting. I knew then that Hughie was dead, because that’s where he had been,” she said.

Many of those present on the night were unaware of where the exits were located in the club. The large numbers attempting to find a route out of the building as the fire gathered momentum led to a “crush” and a “stampede”, with people falling in the darkness in their haste and others forced to walk over them as they lay on the ground.

"I was knocked to the floor, I got up and made my way, mostly being pushed along with the crowd towards the main door. There were three or four people on the floor and there was no movement from them. There were people climbing over them, and I did the same," Kathleen Deeney told the inquest.

Donna Mayne described how within two minutes of first seeing the fire, the lights went out and she was lifted out of her shoes by the force of the crowd and carried towards Exit Five.

“I just remember the blackness, the darkness, the extreme heat,” she said. “This quick flash of the 20 years of my life went before me.”

Patricia O’Connor, just 16 at the time, could feel something like “tar” or “oil” dripping on her as she tried to escape. She said the drops were “big enough to burn the whole of my arms, the whole of my back, my chest, my neck”.

The teenager managed to make her way to an exit by crawling and shuffling along the floor. She sustained burns to 52 per cent of her body.

Paul Byrne told of seeing “black balls of fire dripping down on people”, going on to describe the screams of those trapped in the toilets as being akin to “people being put into the gas chambers”.

“It was an horrendous thing. It will be with me until the day I die,” Mr Byrne said.

Marie Hogan also gave an account of “the ceiling dripping down” and “sticking to people”. “You’d try to brush it off, but it was hot and sticky, and even when some people got outside, there was still smoke coming off them from the bits of ceiling stuck to them,” she said.

Benny Murphy told of the trauma he experienced after seeing a girl on fire in the burning building with no one able to help her because the exit door was on fire.

“Every day I have to wake up to the memories of this girl in the fire exit,” he said.

Some of the most emotional and affecting testimony during the inquest came from survivor Antoinette Keegan, who has campaigned for decades for fresh inquests after she lost her two sisters Martina and Mary in the blaze.

Ms Keegan told how she had a clear memory of her sisters and their friend Mary Kenny, who also died, holding hands on the ground before she lost consciousness. The group were just six feet from Exit Four when they were pushed to the ground and trampled on.

“My last words I ever remember saying in there before I lost consciousness was: ‘Oh God, help us’.”

“I was on the ground, I couldn’t get up, with my sisters. We were all holding one another’s hands,” said Ms Keegan, who was 18 at the time.

“It was just like a fireball that came down and it was coming towards us. I remember putting my hands over my head.” She said the last thing she remembered was being “knocked out”.

A man, whom she later learned was Thomas Larkin, managed to drag her outside to safety. She was still clutching on to her sister Martina as he pulled her outside and he had to kick her hand away to get her out.

Ms Keegan was brought to hospital by ambulance where she was put on life support. It was almost two weeks before she found out her sisters had died.

“I felt so guilty,” she said. “I never even said goodbye. I wasn’t even at their funeral.”

Trapped like rats

Before the fire started, 16-year-old lounge girl Siobhan McConalogue encountered something crucial. Siobhan had worked in the Stardust and got into the Valentine's Day disco for free through the staff entrance at the Lantern Rooms.

“I had met somebody that evening that I was chatting to, and I remember standing talking to him and playing with the chain on the door as I was talking to him…I was actually playing with that chain as I was speaking to him and that is a memory that will never leave me,” she told the inquest.

She said she believed she saw this chain and padlock on Exit Four before the dance competition took place.

Again and again, the inquest would hear direct evidence from survivors that there were chains and locks on the exit doors of the Stardust.

A total of 271 people, representing the majority of the survivors, managed to escape through the main entrance - Exit Two. However, the inquest would hear of the panic that set in when movement out of this exit stopped.

Doorman Frankie Downes, who was manning the main entrance, told gardaí that at around 12.30am he locked the door, removed the key and kept it in his pocket.

He said he did this because the glass in the door was broken and he believed someone could have put their hand in and opened the door. He said that sometime between 1.40am and 1.45am, he opened the double door on both sides and the crowd started to “rush forward” from the club to get out.

In a statement, witness David Bell said that around 1.30am, 10 minutes before the fire was noticed inside the club, he could see that a Chubb lock was in place locking the main exit door.

James Feery said he ran to the hallway of Exit Two only to find "people were jammed in and there was no movement". He said the whole place then filled with fumes and people began collapsing.

“My hair got singed with the heat. There was complete darkness, and I realised that the front door was shut... There were people lying all over the floor of the hallway and others walking over them,” he said.

Mr Feery said that the doors were then opened, which caused “a big heave” that carried him with the crowd out into the open.

Anthony McDonald had run to Exit Three, where he tried and failed to unwrap a chain on the door. He said he held a lock in his hand and was sure that the door was “definitely locked”. Christine Fullam said that after the fire started, she and her friend headed for the same exit, where she saw “a brass padlock on the door”.

In his original statement, Trevor King, 17 at the time, said he and his friend also went into the passageway to Exit Three to find “ten or 15 fellows” ahead of them.

“I heard someone say, ‘Jesus Christ, the doors are locked’,” Mr King said. He said people ran at the door and it burst open, but when they got outside there was also a van backed up to the steps.

“The crowd stopped for a couple of seconds as we were all jammed in. A couple of fellows climbed over the railing and I got over too,” he said.

Brian Baitson, who moments earlier been dancing to Lorraine, said he ran to Exit Four where six or seven people were attempting to open the door. Despite vigorous pushing and pulling it wouldn’t budge, he said. He kicked the door in frustration.

Anthony Byrne also told the jury of his failed attempts to open Exit Four. Anthony was physically strong at the time, as he was training as a boxer and was a member of the defence forces. Despite this, he was unable to force the exit open.

In his original statements to gardaí, Mr Byrne said he went to Exit Four where there were about 15 people trying to open the door. He said some of them were “going mad” and “punching and kicking the door” in an effort to open it.

He said he tried to force the bar up towards the ceiling and although it moved a little, ultimately “the door would not open”. He said he remembered seeing a padlock on the door but could not recall a chain across the bars.

“The door did not open any bit…There was panic at the door and I thought I was going to be killed.”

Mr Bryne said he began looking for another exit but by that stage he was in severe pain. He thought he was wearing gloves but subsequently realised what he was feeling was his skin coming off. He said at this point he “couldn’t stick the pain anymore” and believed he was going to die.

He described to the jury how he decided to walk back into the smoke to knock himself out.

“So I walked into the smoke, took a mouthful and said to myself ‘Dear God no, not this way.’ He said he made it to Exit Five, where a bouncer pulled him out. He believed he was the last person to escape through that exit.

A large group formed in front of Exit Four before it too was eventually opened.

Anthony, whose shirt was “burned off” his body, would spend two weeks in hospital being treated for burns to his hands, arms and face.

He became upset as he told the inquest: "We were actually going mad in there. We were trapped like rats."

Having also been unable to escape at Exit Four, Pauline Jenkins ran to Exit Five, only to find it too was closed. There was also a container of bottles at the exit. Another witness at Exit Five said they saw a bouncer kicking a large padlock off the door and that it took him about three minutes.

The door eventually opened and Pauline was carried by the crowd outside, where she would see the large white van that had been encountered by Trevor King parked up to the steps of Exit Three.

In his later evidence to the inquest, Stardust Manager Eamon Butterly would agree that Exits Two, Three and Four in the nightclub could be considered “a fail”.

Mr Butterly was also shown a map highlighting that in the area between Exit Five and Exit Three, 24 bodies were located - half of those who died - while eight bodies were found in a cluster in front of the bar.

“I’m suggesting that those people died because Exits Three, Four and Five were locked when the fire broke out; they could not escape,” Des Fahy KC told Mr Butterly.

“I deny that,” Mr Butterly said in reply.

Pandemonium

The horror did not end for those who made it out of the Stardust, with many who escaped risking their lives to help those still inside.

James Cumiskey described hearing the screams of people trapped in the toilets as he attempted to break the windows and told how his efforts were fruitless because there was a steel plate in the way.

Mr Cumiskey, who was just 18 at the time, cried as he told the inquest: “You could hear the screams. There was nothing I could have done”.

Donal Clinch, who was 19 at the time and in the company of one of the people who lost their lives, John Colgan (21), gave evidence that he helped to pull people out of the burning building.

“You got down on your hands and knees, you would search around with your hands, and someone would hold you, because if you went back in, you wouldn’t have got back out,” he said, explaining how someone kept a grip on his legs to keep him tethered to the outside.

The jury also heard from Paula Toner, who was 17 at the time and had escaped through the main door. Ms Toner said that only the left-hand side of the main entrance was open initially, before someone kicked the right door out and “people just kind of fell out”.

“I could see fellas and girls banging at the windows of the toilets. A couple of fellas got up on the windows on the outside and broke the glass of the windows. I could see people’s hands sticking out through the window.

She said that outside, survivors broke the glass in the toilet windows and were shouting at the people inside, who were sticking their hands out for help. Those outside told the trapped to put their heads down the toilets. There was an attempt to pull the toilet window bars off using ropes tied to a van, but the bars would not budge.

"There was pandemonium, and then everything just went quiet," Ms Toner said.

"The silence just went through everyone that was outside, the whole place just went deadly quiet, because the hands disappeared and the shouting stopped, and we knew what was basically happening inside.”

Arms around each other

The first call to emergency services about the fire was made by barman Laurence Neville to Dublin Fire Brigade at 1:43am, three minutes after the blaze was noticed by those inside the club.

The first firefighters arrived at the Stardust at 1.51am, with a total of 34 firefighters eventually deployed.

Dermot Dowdall, a then 26-year-old who was on duty at Tara Street Station that night, also received a call from John Fitzsimons, a fireman who worked as doorman at the club. He could hear chaos in the background as Mr Fitzsimons immediately alerted him to the seriousness of the blaze and told him to escalate the call as hundreds of lives were at risk.

He and a colleague jumped in an ambulance and rushed to the scene. As they dismounted the vehicle, he said they were confronted with absolute “mayhem” and people running in all directions looking for friends and family.

Sub-officer Brian Parkes, who by 1981 had 15 years’ experience as a firefighter, said he left the North Strand Fire Station in a tender at 1.46am.

He and his crew had no information about the fire but as they made their way to the scene, they could see flames coming through the roof of the Stardust.

When they arrived at the club, crowds came up to the windscreen of the fire engine and began “thumping on it”, pointing to the fire to tell them people were inside.

“I remember saying to the driver be careful we don’t knock them down because they were just literally milling around…they were in an awful state,” he said.

Patrick Hobbs, who was the acting Station Officer at Tara Street on the night, said when he and his crew initially got to the scene “there was no chance of search and rescue because it was an inferno”.

He said he went over and spoke to people trapped in toilets but “it was impossible” to do anything to help because “there were steel bars and plates welded to it”.

The inquest would heard that the firefighters called to the scene succeeded in rescuing a number of people from the burning building.

Having been told that people were trapped near Exit Two, Sub-officer Parkes climbed a ladder and handed in a hose to another firefighter.

“When I got in I noticed it was a storeroom,” he said. “It was very hot, very smoky but you could just about make your way in.”

He said another firefighter, Noel Hosback, came over with a survivor.

“I just grabbed them and said ‘right come with me’ and I ran backwards down the storeroom, up to the window.”

He said he then “hooshed” the survivor out the window and repeated this three times.

Sub-officer Parkes said by this stage it was still hot but the smoke had cleared substantially and he could see around. He went back down and Mr Hosback told him everyone was out of the toilets.

He said they went to the Stardust Ballroom stage, where the crew were hosing down.

“As it cleared, I began to see exactly what was involved, what had happened,” he said.

Sub-officer Parkes said he looked down to a room behind the stage and when he went in, he discovered there was a “pile of bodies” inside.

“The top three or four I should hope were alive,” he said. “I called immediately and the lads came pouring in and we grabbed them and brought them out.”

He added: “That was the last of the people alive, I think, taken out of the Stardust.”

Sub-officer Parkes said he then went to Exit Four, where he found the right hand door was closed with a chain on it. He said he gave it a kick and it “went flying open”. He said the chain was hanging looped on the bar.

Patrick Colleran, the senior garda officer on duty at the communication centre in Dublin Castle that night, said 'stage one' of the Major Accident Plan was put into operation at 2.06am, and he directed the implementation of 'stage two' at 2.12am on foot of information from the garda officer in charge at the scene.

By 2.20am, the control centre received word from the scene that the fire was under control and all the injured had been removed to hospitals. The work to locate and remove the bodies of those who had perished now began.

“It was gruesome work,” Mr Dowdall told the jury, describing finding a group of victims “huddled together” in a circle on the dance floor.

“They were caught out by the speed of events,” he said. “They grabbed each other, got their heads down and didn’t know much more after that.”

The firefighters had to untangle victims from the wires that had come down from the roof before lining up the bodies outside.

Sub-officer Parkes told how, as he was leaving through Exit Five at the very end of the search operation, he discovered the torso of a victim behind the door and brought it outside to an ambulance.

Firefighter James Tormey found two young people fused together with their arms around each other. He believed they were “trying to comfort each other before they met their demise”.

They were all burnt beyond recognition

He found another body, wearing a red jumper and a gents watch, at one of the exit doors, who was just “two or three steps” from safety.

The jury heard the evidence of a number of firefighters who were not available at the inquest, so their statements were read out by members of the coroner’s legal team.

“They were all burnt beyond recognition; I could not tell if they were male or female,” said Frank Matthews, a firefighter with 17 years’ experience.

“All of these bodies were badly burnt and completely beyond recognition. Some of the bodies were in bits,” said James Rowan.

At 2.54am on Valentine's Day, the last pockets of burning had been extinguished and the fire was deemed to be officially out.

Before the fire

The fresh inquests into the Stardust fire, long campaigned for by the families of the victims, began in April 2023 and sat for close to a year. The evidence heard was vast, with the jury presented with evidence from 373 witnesses, three forensic pathologists and three fire experts.

The panel were shown photographs, aerial footage of the complex taken by helicopter and a virtual recreation of the Stardust. They were also read extensive testimony and statements given to a 1981 tribunal of inquiry into the Stardust fire before Mr Justice Ronan Keane.

The jury heard that there was a suspended ceiling inside the Stardust, while carpet tiles of a polyester fibre on a PVC backing covered some of the walls. When not at capacity, the West and North alcoves could be closed off using roller blinds.

There were fire alarms behind breakable glass at 11 positions, seven in the ballroom and four at other locations.

Concerning means of escape from the building, the jury heard of the eight exits from the ballroom, including the numbered emergency exits, as well of three exits from the Lantern Room, three from The Silver Swan and an exit from the kitchen.

The jury also heard that steel plates had been welded internally to the frames of the toilet windows and vertical bars welded to the outside of the windows. The steel plates had been fitted by the management approximately six weeks prior to the fire for security purposes.

Architectural draftsman Harold Gardner worked on the revised plans for the Stardust, which were approved in January 1978. The inquest heard that Dublin Corporation's Senior Building Surveyor visited the complex on three or four occasions, while the fire service did not carry out any inspections.

The jury heard that Martin Donohue, the Corporation's Inspector of Places of Public Resort with special responsibility for electrical matters, carried out seven inspections of the building between 1979 and 1981. As an unavailable witness, Mr Donohue's statement was read to the jury.

He reported numerous issues, including instances where a door in the Lantern Room was not opening fully, loose tables were obstructing a passageway to an exit and a panic bar on an exit door was sticking, preventing it from opening easily.

On September 4th, 1980, he found that an exit door in the Silver Swan bar was chained and locked. He said he drew this to the attention of Stardust manager Eamon Butterly, who said he was not aware that the door should be kept open at all times but would have it opened immediately.

He visited the Stardust on November 24th, 1980 to find that Exit five was chained and locked, while a bolt on the panic bar was broken and a piece hanging loose.

Mr Donohue said he inspected the Stardust during a concert on January 15th, 1981, when he believed the number of people present was in excess of the 1,400 permitted by licence. He said in his experience, the number was nearer to 2,000 and he found it difficult to move from one exit to another due to the large volume of people present.

The jury heard that Mr Donohue was not the only person to flag an issue with doors being locked while patrons were on the premises.

On two occasions in July 1980, Garda Sergeant Thomas Callanan, who was stationed at The Bridewell, visited the Silver Swan bar, where he witnessed a fire exit door locked while patrons were in the venue. He said he pointed out the danger on both occasions to a bouncer.

Sgt Callanan was again at the same venue in August that year, where he noticed the emergency exit was still locked. He spoke to a manager and “pointed out the danger should a fire occur in the premises”.

“I informed him that if the lock was not removed before the date of renewal for the licence of the premises, I would bring to the notice of the court the fact that the emergency exit was locked,” he said in a 1981 statement.

The sergeant said he visited the premises in the last week of August 1980 and saw the lock had been opened on the door and was hanging on the end of a chain from the bar on one side of the door.

The jury also heard a 1981 statement by Diarmaid H. King, the Senior Building Surveyor with Dublin Corporation's planning department. In the statement, Mr King said he had no knowledge of when steel bars and plates were fixed to the toilet windows in the Stardust, but he said that the windows were not considered a suitable means of escape.

“I considered the number of exit doors was more than ample as a means of escape,” he said.

Mr King went on to say he had no idea that exit doors were being kept locked for up to two hours during performances at the Stardust.

Asked at that time about the January 1981 inspection, in which it was noted that an exit passageway at the side of the stage was obstructed and there was overcrowding in the cabaret room, Mr King confirmed that this constituted “a very serious infringement of the by-laws”.

A reply to these concerns was sent to the planning department by Stardust manager Eamon Butterly, who said the back exit had been cleared. Mr Butterly claimed that tickets had been forged for the show on that night in January, which accounted for the number of people present.

'Pretty horrendous fire risk'

During the inquest, it emerged that the Stardust was twice turned down for insurance and had been considered by an assessor to be a "pretty horrendous" fire risk.

In his original statement, which was read into the record by the court registrar, Richard Williams said that from 1961 to 1997 he was with Hibernian Insurance, where he had worked in underwriting until 1981.

Mr Williams said that in 1979, he was asked to quote for fire insurance on the Stardust but, after reading a fire survey on the premises, declined to do so. In 1981, he was appointed a fire surveyor and was sent out to assess the property.

“I duly reported on the fire risk, which I deemed as pretty horrendous and recommended that we did not quote, so it was turned down again,” he said.

Mr Williams said that a new cold room installed behind the bar had been built with aluminium and polystyrene foam insulation, which was considered “highly combustible”.

Mr Williams said that he also saw a push bar exit which was chained. He said that when he asked about it, he was assured that the chains were removed before the premises were opened to the public.

As draftsman, Harold Gardner was an unavailable witness, his statement and extracts from his questioning during the 1981 tribunal were read to the jury.

Mr Gardner said that he was not involved in the decision to put carpet tiles on the walls of the Stardust and that he did not consider getting full information from the manufacturers of any products used. He said that he did not specify what the foam seats should be made of, nor did he specify that they should be fire-resistant.

Mr Gardner was asked about a planning condition that stated if a building contained flammable materials, then it should have a sprinkler system installed.

“I’ve got an idea that I mentioned it on one occasion,” replied Mr Gardner, going on to say that he believed Company Director Patrick Butterly, now deceased, was not interested in the system.

Job lot

During the 1981 Tribunal of Inquiry, evidence was given that the carpet tiles on the walls of the ballroom had contributed most to the spread of the fire.

Declan Conway, a sales representative for the company that provided the tiles for the Stardust, said that drapes for the walls were discussed, but ultimately wall carpet tiles were used.

He said he spoke to the manager of the Stardust, Eamon Butterly, who requested that Mr Conway obtain a fire certificate from the manufacturer of the tiles. Mr Conway said he was able to get a certificate that met the British standard specification.

In the original planning for the Stardust, a requirement from the chief fire officer was for all internal wall and ceiling linings to have a minimum of 'Class 1' surface spread of flame rating. The inquest jury heard that a surface spread of flame test was carried out and found that the carpet tiles were Class 4, not Class 1 as required.

“I’m not aware of that, and I can only reiterate that the specification, as far as I was aware and told, met the British standard specification,” said Mr Conway.

“Did anyone say to you: ‘Are we sure this is appropriate if these things are placed on walls?’” asked Brenda Campbell KC, for a number of the victims’ families.

“No, it never crossed my mind,” said Mr Conway.

The inquest later heard that the company that produced the carpet tiles did not recommend their use on walls and had sold them off as a “job lot” because they were being discontinued.

Graham Whitehead, Company Secretary for UK-based Illingsworth and Company Limited who supplied the 'Stateroom' tiles used on the walls of the nightclub, told the 1981 Tribunal of Inquiry that the company had never advertised the tiles for use on walls.

“We could not stop it being done, but we have not recommended it,” he said.

Mr Whitehead said that the 'Stateroom' tile “had reached the end of its life” and the company was "jobbing it off" as there was another product on the market to take its place. He told the tribunal that this was reflected in the price.

The tribunal heard the original price of the tile was one pound 28p, but it was sold off at 75p per tile.

In his evidence to the tribunal, Mr Whitehead said the company would never provide a fire certificate as “we are not an appropriate body to issue one”.

He said the document sent to Mr Conway was not a fire certificate but was “for information”. He confirmed to counsel at the inquiry that his company did not know what purpose the cert was to be used for when it was sent.

He said he had traced a letter addressed to Mr Conway dated January 26th, 1978, which referred to the results of a flammability test the salesman had recently requested.

Mr Whitehead said the document enclosed referenced flammability on carpet tiles laid on floors and came from their laboratory. He said this was a standard document circulated amongst the company’s customers upon request.

Asked what the function of the document was, Mr Whitehead said: “This is to help architects to establish fire worthiness of carpet tiles”.

He said the company did not produce carpet tiles for use on walls. Asked to express an opinion as to whether the tiles would be suitable for use on the wall or not, Mr Whitehead said he had asked his company’s technical department about this, and they had said that “under no circumstances would we recommend these tiles for wall covering”.

'Watching a disaster movie'

Over the course of the inquest, the jury heard evidence from witnesses who saw sparks raining down from the Stardust ceiling during live music concerts in the weeks before the fire, as well as those who had smelled smoke.

Patrick O’Driscoll gave evidence that he was part of an Elvis Presley tribute band that was playing in the Stardust in February 1981. He said he saw “a shower of sparks” coming from the ceiling at the backstage area.

“It was one quick shower. I kept playing, as I thought it was just a power surge,” he said.

He described the sparks as “whitish with a yellowish tint” and as coming out in an arc of three to four feet.

“It was just a shower. If you were passing a building site and saw a welder and he was welding, that kind of shower, or maybe watching a disaster movie, something like that,” he said.

The jury heard evidence from Suzanne McCluskey, who attended a concert at the Stardust on January 15th, 1981. In her original statement made after the Stardust fire, Ms McCluskey, who was still at school at the time, said that during the concert she noticed “sparks flash down from the ceiling”. She said the interval between flashes was about a minute to two minutes, and she noticed it for about ten minutes in total.

“The flashes I saw were a purple colour, they were not a series of flashes, just an odd purple flash,” she said.

James Murphy, who worked as a glass washer at the Stardust from October to December 1980, while studying for his Leaving Cert, said in a deposition that about a week before he stopped working at the Stardust, he noticed a “strong smell” of burning.

He said he was in the main bar getting things ready for the night with one of the barmen who asked him if he got a smell of smoke.

Mr Murphy said at this point he noticed a smell like “rubber burning”. He said he stood on a chair at the middle of the back balcony and could still get the smell. He then went up to the lighting room which was directly over the room where kegs were stored for the complex and when he opened the door he got a stronger smell.

He said he went back to work and the smell faded away after a while.

In a deposition, Elaine Stapleton, who was a waitress in the Stardust, said that four weeks before the fire, she saw smoke coming over the top of the dispense bar on the premises.

“When I saw it first, it was dense and then it thinned out. In my opinion, the smoke was coming from out over the front wall of the dispense bar. Someone said the smoke was from the heating. I am satisfied it wasn’t cigarette smoke, dust or fog. It wasn’t steam either,” she said.

'An Eamon Butterly man'

Of crucial importance to the inquest were the practices of keeping exit doors in the Stardust locked when patrons were on the premises and of draping padlocked chains over the panic bars of these doors to give the impression they were locked. The latter process was referred to as “mock locking”.

Floor manager Phelim Kinahan, who had overall responsibility for security at the Stardust, was called to the witness box in June of last year.

In a second statement to gardai, Mr Kinahan said that at around 9pm on the night of the fire he went into the main bar and switched on the heating for the Stardust. He said there were three switches on the wall of the bar about six foot, six inches from the ground. He said the switch on the left was not working and he had been told by Eamon Butterly a few weeks previously not to touch it.

He said there was a sign underneath the switch proclaiming that it was not to be touched by anybody - only Eamon Butterly and one other person.

Mr Kinahan said on the night of the fire, sometime after midnight, he went to Exit One and noticed that the upright bar on the doors was missing and that the doors could not be locked. He said he walked out this door, along a passageway towards an outer exit door.

He said he went to Exit Four and saw that the chain was in an unlocked position. He said the chain was hanging from one of the bars and he put it across the second door to “give the impression” that both doors were locked together.

Mr Kinahan said he spoke to Eamon Butterly in the Swan Bar for about five minutes at around 1.20am or 1.30am and was about to go into the Stardust when he met a barman who told him there was a fire.

He said he went out and saw that the curtain nearest the bar was up. He said as he was looking at the fire, Eamon Butterly was standing beside him and he heard him say: “The bastards started a fire” or some words to that effect.

In a further statement, Mr Kinahan said he remembered glass washer James Murphy telling him about a smell some months before the fire. He said he also got the smell, which was like rubber burning. The floor manager said he turned off the heaters and the smell disappeared.

Mr Kinahan said he reported the smell to Eamon Butterly and that the following day, Mr Butterly told him that he had to buy a new motor for the heater, which cost him a fortune.

In his evidence before the inquest, when Mr Kinahan was asked about the policy of draping chains over doors, he said that when the Stardust was "active" the locks were taken off the chain, but the chain was “left hanging” and thrown over the bar of the exit doors.

“If you pushed it, it would open,” he claimed. He confirmed that this process was designed to make it look as if the doors were locked. Mr Kinahan said he didn’t know how this practice came into place.

When asked if he felt any responsibility to the hundreds of people who had paid in to the Stardust that night, Mr Kinahan replied: "Not really, no."

Mr Kinahan said that the policy of draping chains over fire doors was in place before he started working at the club and it was “common practice” in the industry. He confirmed that he had never received any instruction on fire drills.

A bizarre episode also unfolded during Mr Kinahan’s video-link evidence.

During a recess, it was alleged that Mr Kinahan was heard on microphone speaking to a person off-camera, who said the doors in the nightclub were locked on the night of the fire, to which the witness was said to have replied: “It’s nothing to do with me, so I’m not saying that.”

Mr Kinahan’s microphone had been left switched on during the recess, and when the court resumed, legal counsel told the jury that a disagreement was overheard between Mr Kinahan and someone not visible on-screen.

“You were heard having a disagreement with someone. The person who overheard it heard a person say that the doors were locked, and you said: ‘It’s nothing to do with me so I’m not saying that’,” Des Fahy KC, acting on behalf of a number of the bereaved families, put to Mr Kinahan.

“I don’t remember saying it,” replied Mr Kinahan.

“If the doors were locked, is your position that it was nothing to do with you?” asked Mr Fahy, to which the witness replied that it was.

“As far as I can remember, all the exit doors were open,” said Mr Kinahan.

Mr Fahy asked him about the morning after the fire, when staff members were asked to go to the Stardust to make a statement to the management’s solicitors. He asked if the reason for this might have been that statements were required from staff to help with a compensation claim.

“I do not know fully. Eamon Butterly did his own thing,” replied Mr Kinahan.

Mr Fahy put it to Mr Kinahan that the witness was “an Eamon Butterly man” in 1981, and he remained “an Eamon Butterly man” now.

“I think so,” replied Mr Kinahan.

The following day Mr Kinahan resumed his evidence in the company of a "legal advisor", whom the coroner told the jury was there for "moral support".

Continuing his evidence, Mr Kinahan said there was a concern about people getting into the Stardust without paying, so the practice was for the doors to be locked or appear locked by looping a chain over the bars.

Dáithí Mac Cárthaigh BL, representing one of the families of the deceased, asked him if it was ever discussed that a better solution would be to put a man on every door.

“It was mentioned, but when they worked it out, to the best of my knowledge, it came out too expensive to have a man on every door,” replied Mr Kinahan.

Mr Mac Cárthaigh asked if it was deemed that a man on five doors at 15 pound each was too expensive to put the best practice in place, to which Mr Kinahan replied it was.

Mr Mac Cárthaigh said evidence was given to the 1981 tribunal estimating there were 775 paying customers on the night at three pounds each, making a total of 2,325 pounds, which he described as “a small fortune” in 1981. The witness replied that this was not a small fortune as there were a lot of expenses to be paid.

Mr Mac Cárthaigh asked the witness about Eamon Butterly allegedly saying “The bastards started a fire” or words to that effect. Counsel asked Mr Kinahan what he thought was meant by this.

“There was a certain amount of people around the area of the fire, and I think he thought the same as I did; that the people started the fire just to distract the barmen so they could rob the bars,” replied Mr Kinahan.

“I find that answer disgraceful,” said Mr Mac Cárthaigh.

An enormous shadow

The evidence of former doormen who worked at the club failed to shed further light how staff viewed the precise status of the doors at the time of the fire. Even deputy head doorman Leo Doyle told the inquest that he could not say whether the exit doors were unlocked when the fire started.

“We used to unlock the doors, chain the two chains together with a lock and flip the chain over to give the impression they were locked,” he said.

“You can’t say if they were unlocked?” he was asked.

“I can’t say, no,” replied Mr Doyle.

Bernard Condon SC, for a number of the families of the victims, asked him if he accepted that this practice of “mock locking” the doors was inherently dangerous. Mr Doyle replied that he did not accept this.

Mr Condon said that in a statement made by another doorman, Michael Kavanagh, Mr Kavanagh had said that a number of weeks before the fire, a number of people got in for free through an exit door, that “Eamon Butterly was mad over this” and “instructions came down from the top” that chains and locks were not to be removed from the doors on any night that a disco was on.

Mr Doyle confirmed that if such instructions came down, they “came from the top”.

Michael Kavanagh would prove to be another significant witness.

A junior doorman barely out of his teens in February 1981, Mr Kavanagh made false claims in the wake of the fire which had far-reaching implications.

By his own admission, the doorman had lied when he spoke to reporters outside the Stardust just hours after the fire, telling them he had unlocked the exit doors before the blaze broke out. The 20-year-old doorman again repeated this claim in statements made to gardaí and RTE television on February 16th.

Some hours before he made his initial remarks to journalists, he had been in his friend Michael O’Toole’s house drinking tea with Michael and his father James when he admitted to them that the doors of the club were locked.

After his conversations with the O’Tooles, he left the house with his friend and searched a number of Dublin hospitals looking for his girlfriend, Paula Byrne (19), before returning to the Stardust, where he spoke to the press. Ms Byrne was one of the 48 victims.

During three days of intense questioning from lawyers representing the victims’ families, Michael Kavanagh was repeatedly asked why he had initially lied before subsequently changing his version of events. Over the course of this questioning, Mr Kavanagh said he “wasn’t thinking straight” for weeks after the fire and got “caught up in something that was not my making”.

He also said he was “trying to protect the other doormen” but denied there had been any discussion among them to give a “sanitised” version of events.

The jury heard that the doormen had been summoned to the Silver Swan pub the day after the fire, where bottles of spirits were freely available, though Mr Kavanagh said he had never drunk alcohol in his life.

They had been requested to attend the complex to speak to Mr Butterly’s solicitor and – according to Francis Kenny, another doorman – were told “not to talk to anyone” until Mr Butterly’s solicitor had spoken to them.

Mr Kavanagh was picked up at his home by Leo Doyle and Mr Kenny shortly before lunchtime that day and brought to the Stardust for the meeting scheduled to take place at 2pm. However, the young doorman broke down while he was there and left the premises without making a statement.

It was another two days before he gave an interview to RTE and made a statement to gardaí. The claims Mr Kavanagh made on RTÉ’s Today Tonight programme broadcast on Monday, February 16th, spurred the O’Tooles into action.

James O’Toole went to gardaí the following day and told them that in the early hours of Valentine’s Day, Michael Kavanagh had been in his home and had said that four exits were padlocked and two were unpadlocked.

He said the doorman also told him that the doors were always locked and that he was under instructions to keep them locked.

He said Mr Kavanagh told him: “The poor bastards in there must have died like rats. They couldn’t get out, the doors were chained.”

Michael O’Toole also made a deposition stating that Mr Kavanagh had told him the exit doors were locked.

When the two men’s statements were put to him, Mr Kavanagh said that while he couldn’t remember what he had said in the O’Toole family home, he would not dispute it because “if Michael and his father Jimmy said it, I must have said it”.

The former doorman retracted his initial garda statement on February 19th, because he believed he was being made “a scapegoat” and felt attempts were being made to “blame” him for the doors being locked.

He told gardaí what had actually happened was that at about 9.40pm, he had been about to go around to the fire exit doors and unlock the chains and padlocks when Leo Doyle told him not to unlock them.

He said he decided to go to the gardaí after a conversation with his father gave him “a reality check” about the “stupidity” of what he had done.

Illegal

The following day, the club’s then head doorman, Tom Kennan, told gardaí that he had unlocked the doors at around midnight on the night of the fatal blaze.

This was Mr Kennan’s second statement to gardaí. In his initial statement, made hours after the fire, Mr Kennan made no reference to opening the doors.

At the 1981 Tribunal of Inquiry, Mr Kennan, now deceased, confirmed that it was not his “usual practice” to open the exit doors and said that he had only done it once before.

Mr Kennan admitted to the tribunal that he knew the practice of locking doors while people were inside the complex was illegal.

He told the tribunal that the reason he did not go to Eamon Butterly, who was his nephew, and tell him the practice of locking doors was not only illegal but also dangerous was because Mr Butterly “was aware of it”.

“And you knew he was aware of it?” he was asked by counsel.

“Oh yes,” Mr Kennan replied.

The head doorman also claimed that, immediately after the fire, he had said to Mr Butterly: “Thank God all the exits were open”.

Mr Kennan told the tribunal that the system of chaining doors “worked very well” and “a lot of people got out of the premises” on the night of the fire. He said he could not identify any deficiencies in the procedures.

“Your system of chaining doors and opening doors worked well?” he was asked. “You’ve no criticism to make of that?”

“I’ve not really, no,” Mr Kennan replied.

Change in policy

In his evidence to the inquest, Michael Kavanagh said there had been a “change in policy” about six or seven weeks before the fatal fire, when he was told that exits were to remain locked until 12am.

The directive was implemented because Eamon Butterly was “basically pissed off” that people were gaining access to the premises through side doors, he said.

On one occasion, he said he had removed the chains and locks from the fire exit doors during a disco only to find later that night that they had been relocked before the event was over. He said it was after 12.30am before he discovered that the doors had been relocked.

During his second day in the witness box, Mr Kavanagh was asked by barrister Des Fahy whether the policy of keeping doors locked until after midnight came about following an incident on St Stephen’s night 1980, when doormen were found to be allowing people into the club and keeping the money for themselves.

Mr Kavanagh said he didn’t “know anything about that” because “I was not involved in it”.

Mr Fahy said Deputy Head doorman Leo Doyle had previously admitted during his evidence to the inquest that people had been let into the complex on St Stephen’s night through the Lantern Rooms by doormen and that he [Mr Doyle] and other doormen got money out of this.

It was put to Mr Kavanagh that Mr Doyle had named him as someone who had been on duty in the Lantern Rooms that night. Mr Kavanagh was emphatic that at “no stage” was he “ever in any receipt of any money”.

Mr Kavanagh was again questioned about why he had initially lied about opening the exit doors. Asked if the other doormen were on his mind at that stage, he replied: “You do have some loyalty towards them, yes.”

However, he said this changed after doormen Leo Doyle and PJ Murphy visited his home while he was out and spoke to his parents.

Mr Kavanagh’s father, Patrick, now deceased, told gardaí in a statement made on February 27th, 1981 that Mr Doyle and Mr Murphy had called to his home on February 18th. He said that the man called PJ told him that head doorman Tom Kennan had made a statement to police that he had opened the chains on the exits doors on the night of the fire at the Stardust. He asked him to tell Michael “for the love of God to retract the previous statement he had made to the police”.

Mr Kennan did not in fact make his statement to gardaí until February 20th.

“Did you realise then, along with your father, that these men didn’t have your back at all?” asked Mr Fahy.

“Exactly; when I had the conversation with my father and my sister, I knew I had to start thinking about me and that’s what I did,” Mr Kavanagh said.

Mr Condon put it to the former doorman that Leo Doyle and PJ Murphy “became worried” that he would not “stick to the story” that he had unlocked the doors and it was at that point that they had visited his mother and father.

Counsel said this was why they “needed to put head doorman Tom Kennan in as the man who unlocked the doors”.

Counsel said Mr Kavanagh’s father was told “quite extraordinary things”, including that his son “would be up for perjury”.

On his third and final day in the witness box, Mr Kavanagh denied that he was “put up to” saying he had opened the doors to advance the interests of “other parties” or that there had been any discussion amongst doormen that they would give a “sanitised” version of events.

Mr Condon said the real issue everyone was grappling with was what had happened between the time Mr Kavanagh was sitting at the O’Toole's table telling them the doors were locked, and telling the press at the Stardust that the doors were unlocked.

“What happened in that intervening period to cause that?” he said.

“Like I’ve been saying, I’ve no idea,” said Mr Kavanagh.

“You understand that that lie, as it was called, caused an enormous shadow or fog to fall on the investigation and I don’t think it’s ever been lifted," counsel said.

“I don’t know what happened,” Mr Kavanagh replied.

Counsel said the “extraordinary thing” was Mr Kavanagh had then gone on RTE and repeated the lie to “the whole country”.

“What was going on?” asked Mr Condon.

“I’ve no idea,” Mr Kavanagh replied.

The question, Mr Condon said, was whether Mr Kavanagh was “an innocent abroad, a fantasist having a rush of blood to the head” or whether this was “a conspiracy” that was “being done to advance the interests of other people”.

“I don’t know why I did what I did. There was no conspiracy on my part. I don’t know,” he said.

'There were always chains and locks on the doors'

The statement of another doorman, Michael Griffin, was also read to the jury. He said that on one occasion, he was told by his boss to remain at one of the exit doors, which was locked and chained. He said he was told only to open the door in an emergency.

The jury heard the evidence of another unavailable witness, doorman John Fitzsimons, who said he was aware of the practice of looping chains and locks around the bars of exit doors so as to give the impression that the door was locked. He accepted that this could have been a very unsafe practice from the point of view of fire safety.

The jury also heard evidence of doors being chained from a number of former waitresses. Phyllis Cobbe, who worked in the Lantern Rooms section of the Stardust, told the jury that: “There were always chains and locks on the doors.”

Paula Foy, who was 17 at the time of the fire, gave evidence that she remembered the chains were "always on" the doors, but she said she did not know anything about when they were locked or unlocked.

Patricia Gallagher said that the doors to Exit Five were locked when she got to them on the night of the fire. She said there were chains on the door and “they were always on the doors”. She said this was because “people were coming in and opening the doors and letting their friends in”.

Joseph McGrane, who was a glass washer in the Stardust, said that during the evening, he saw a doorman checking the locks on Exit Five. He confirmed that there were chains and locks on these doors.

Cormac Rose, who was 17 when he worked in the Silver Swan bar in the Stardust complex, said he had “heard some hearsay” from the door staff about the procedure in the Stardust of exit doors being chained and locked.

“They were saying that the policy was changed, they were being asked to chain the doors between certain hours of the night to stop people getting in without paying, and then that policy changed to chains being draped over the doors,” he said.

And Trevor King, who was 17 at the time and used to work in the Stardust, told the jury that the practice of locking the doors was taking place up to two years before the night of the blaze.

“The exits were always locked by chains and padlocks. I think it was to keep people from getting in for nothing,” he said.

Eamon Butterly

The longest evidence given by a single witness was that of Eamon Butterly, the manager of the Stardust nightclub at the time of the fatal fire. Mr Butterly was in the nightclub when the fire broke out but managed to escape the building.

He was examined over eight days by various legal representatives about the operation of the nightclub, where again the practices of keeping exit doors locked when patrons were on the premises and of “mock locking” were of central importance.

For the families of the Stardust victims, one of the more distressing features of the original tribunal in 1981 was a finding that the fire was probably started deliberately.

This conclusion was always disputed by the families, not least because it allowed the Butterly family in June 1983, to bring a claim seeking £3 million from Dublin Corporation. A Circuit Court judge found in their favour and the family was ultimately awarded damages of £581,000.

Forty years later, as the still-grieving families gathered in the Pillar Room of the Rotunda Hospital, Eamon Butterly told the inquest that he stood over his company’s malicious damage claim on the fire. In a 1981 statement, he had said he believed that the fire was started deliberately.

In his original statement to gardaí, Mr Butterly said he was the managing director of Silver Swan Limited, the company that managed and ran the Stardust club.

He said that at 1.30am on February 14th, he was told by a barman that there was a fire in the Stardust. He said he saw two barmen and a doorman fighting the fire, which was on the seats at the back of a partitioned area.

“I was amazed to see where the fire was as this area had been partitioned off since last Sunday and the Stardust itself had not been used since that day,” he said.

He said he had asked the head doorman earlier if all the fire exits were unlocked, and the doorman replied that they were and he had men stationed at each exit.

“I personally saw that ten of the exits were open,” Mr Butterly said, adding that the head doorman then checked the other exits and said everything was okay.

The jury heard that Mr Butterly told gardaí that the staff were given no specific instructions in the event of a fire.

“I felt that I was not an expert, that I would not be aware of what specific instructions should be given to the staff in the event of a fire,” he said.

Mr Butterly was asked about the company policy about the unlocking of exit doors.

“On Saturday nights or any non-disco night, all the exit doors were unlocked at approximately 7.30pm. On disco nights, Exit Three would be unlocked at 8.30pm. Door two would be opened at 10pm to allow the admittance of the patrons. Door four would be opened shortly before 10pm. The remaining exit doors, namely five, six and one, were normally opened between 11.30pm and 12am,” said Mr Butterly.

“The policy of unlocking the remaining doors at approximately 11.30pm was forced on me by the fact that a large number of people were getting in for free due to the actions of their friends who were opening exit doors from the inside,” Mr Butterly told gardaí.

He said that most doormen had no responsibility for checking if the doors were unlocked, and this responsibility was placed on the head doorman, Tom Kennan.

“At no time since the premises opened in March 1978 were the fire exit doors left locked during the whole of any evening,” he said.

The jury heard that Mr Butterly told gardaí that the separate practice of “mock locking” the doors “originated from the doormen” and was not something he ordered them to do.

He was asked who had decided that a padlock and chain should be attached to one exit door only and the chain draped over the panic bar on the other half of the exit door.

“This practice originated from the doormen themselves. They had used this practice in other places where they worked. I did not order them to do this, but I was aware of the practice and did not stop same,” said Mr Butterly.

A member of the coroner’s legal team, Gemma McLoughlin-Burke BL, asked Mr Butterly about his original statement, in which he had said that Exits Two, Three and Four were usually unlocked before 10pm, and the remaining doors were usually opened between 11.30pm and 12am.

Mr Butterly replied that this was not a policy in the Stardust and that Mr Kennan had told him this was taking place.

“I told him the doors shouldn’t be locked. I never saw the doors locked,” he said.

"You never saw any exit door locked in the Stardust?” asked Ms McLoughlin-Burke.

“No and if I did there would be trouble,” replied the witness.

Michael O’Higgins SC, representing a number of the families, questioned Mr Butterly about this statement.

"From reading that, my impression is that this was something Tom Kennan was doing on his own initiative,” said Mr O’Higgins.

"He was in charge,” said Mr Butterly.

“If what you’re saying isn’t true; you are attacking him in your evidence here because you’re putting the blame on him, and he’s dead,” said Mr O’Higgins, going on to ask: “You wouldn’t be throwing Tom under the bus here?”

“I would not, no,” replied Mr Butterly.

After four days in the witness box, Mr Butterly qualified his direct evidence and told the inquest that the locking and unlocking of exit doors at the nightclub was his "joint policy" with door staff.

Continuing his cross-examination, Mr O'Higgins said there was a conflict between what Mr Butterly originally told the gardaí and what he had told the jury in the inquest.

Mr O’Higgins said that Mr Butterly had told gardaí that “the policy of not opening Exit doors Five, Six and One until approximately 11.30pm was decided on”.

“The policy of doormen circulating the premises after they had finished their duties on the main door was another result of discussions between (head doorman) Tom Kennan, the other doormen and myself,” counsel said Mr Butterly had told gardai.

“Does that say in very bald terms this was your policy?” asked Mr O’Higgins.

“It was saying that I agreed with what they said,” replied Mr Butterly.

“Was it your policy?” asked Mr O’Higgins.

“It was the policy of the security staff and me,” replied Mr Butterly.

“Is that a shift from what you told the jury, when you said this was all Mr Kennan’s initiative?” asked Mr O’Higgins.

“It was Mr Kennan’s initiative,” replied Mr Butterly.

“How much of this policy are you willing to own?”

“I can’t say,” replied Mr Butterly.

Again referring to the original statements, Mr O’Higgins said that Mr Butterly had been asked who made the decision to keep the doors locked as people were getting in for free, to which Mr Butterly said: “I made the decision myself.”

“You’re owning it 100 per cent there, aren’t you?” asked Mr O’Higgins.

“I am, yeah,” replied Mr Butterly.

Mr O’Higgins asked the witness why he was now telling the inquest jury the exact opposite.

“I made the decision with Mr (Tom) Kennan and (deputy head doorman) Mr (Leo) Doyle,” said Mr Butterly.

Mr O’Higgins asked if he believed the evidence he had given the 1981 tribunal and evidence he had given the inquest was the same, to which Mr Butterly replied: “I’ve given the evidence to the best of my ability.”

Coroner Dr Myra Cullinane said that this evidence and the evidence from 1981 was different and she asked Mr Butterly which he now stood over.

“The ones I made here,” replied Mr Butterly.

“In 1981, the decision was made between the three of us, so I went along with Mr Kennan. That’s what I believed last Thursday,” he said.

“It is contradictory alright, yeah,” he added.

'In no uncertain terms'

Mr Butterly gave evidence that the practice of locking certain exit doors at the nightclub for a portion of the evening was only introduced about three weeks before the fire, but the practice of “mock locking” doors had been going on a long time.

Des Fahy KC asked Mr Butterly if it was an unsafe practice to have the doors locked for any period of time.

“It would be, yeah, but the men that were in charge of it were in control that they could open them,” replied Mr Butterly.

“So, you’re accepting that it was unsafe?” asked Mr Fahy.

“I’m accepting that it was unsafe, but Mr Kennan had control over it,” said Mr Butterly.

“In what way was it unsafe?” asked Mr Fahy.

“They shouldn’t be locked, I suppose,” replied Mr Butterly.

Mr Fahy suggested that following the incident on Stephen’s Night 1980, in which it was claimed that some doormen were letting people in, charging them and keeping the money for themselves, there was a change in policy.

He said the policy was changed, from “mock locking” the doors by draping chains over them to give the impression they were locked, to actually chaining them.

“They have given evidence that the change happened because you found out about Stephen’s Night 1980,” said Mr Fahy.

“That’s what they’re saying, I don’t remember that. I would be mad if I knew, but I don’t remember that,” replied Mr Butterly.

Brenda Campbell KC, for a number of the victims’ families, referred to the evidence of Martin Donohue, the electrical inspector who found the exit door in the Silver Swan locked and chained.

"You had been told in no uncertain terms that locks and chains on your premises were completely unacceptable when patrons were there,” said Ms Campbell.

“I accept that,” said Mr Butterly.

“Did you tell your staff that under no circumstances are locks and chains to be on those doors?” asked Ms Campbell.

“Yes; I can’t remember telling them, but if I told Mr Donohue I would tell them, I did tell them,” replied Mr Butterly.

In a tense exchange, Michael O'Higgins SC put it to Mr Butterly that the reason his accounts of events and conversations around the time with the now-deceased Mr Kennan were "so vague and contradictory" was because "they are not founded on truth".

"Are you saying that I am telling lies?", Mr Butterly asked.

"Yes, I am," counsel replied.

"I am not telling lies," said Mr Butterly.

Mr Butterly was also questioned about the use of the carpet tiles on the walls, which the surface spread of flame test found to be of Class 4 rating and not Class 1 as required. The jury heard that in original statements made by Mr Butterly, he said: “I did not know what Class 1 surface spread of flame rating meant.”

Ms Campbell asked Mr Butterly if the price had influenced his decision to purchase these carpet tiles.

Mr Butterly said that “the price would influence all decisions” but it wasn’t “the first thought in my mind.” He said his first thought was to get the walls “covered nicely” and “looking well”.

Ms Campbell put it to Mr Butterly that Graham Whitehead told the 1981 tribunal that his company did not manufacture the tiles for use on walls and would not “under any circumstances” recommend their use in such a manner.

Asked what his answer was to this, Mr Butterly said he “didn’t know that”.

He said he bought the tiles from Declan Conway on the basis that he provided a fire certificate for them. “I know nothing about what he said or did with the company in England…I know nothing about that,” he said.

Asked by Bernard Condon SC, for ten of the families of the deceased, if management at the club were up to dealing with problems that arose, Mr Butterly said: “They weren’t up to dealing with fire, that’s for sure.”

“That’s the truest word you’ve ever said,” Mr Condon replied.

“I’ve said all along we didn’t know how to give the instructions, I wasn’t qualified,” said Mr Butterly.

Something fell through the cracks

Mr Condon put it to Mr Butterly, on his last day in the witness box, that this was his opportunity to say that “something fell through the cracks” and the doors were “not opened” on the night of the fire.

In response, Mr Butterly said: “At 11.30pm in the Silver Swan, Tom Kennan told me that 'all the doors are open'.”

In one exchange, Mr O’Higgins asked Mr Butterly if, as a matter of common sense, there should have been a system in place whereby in the event of a fire the lights would come up, the music would go off and people were to leave the premises immediately.

“Oh yes, if it was now, it would be a completely different situation. Then, there was nothing about that type of thing. At the time, we weren’t given any regulations about that, I wouldn’t know what to do,” said Mr Butterly.

Mr O’Higgins replied that there were lots of laws in place directing what to do, some going back to 1967.

“I didn’t know about them, neither did my father or anyone else, and he was the licence holder,” replied Mr Butterly, going on to say: “I was panicking as well.”

“I fully accept you hadn’t the remotest idea what you were doing,” said Mr O’Higgins.

“I didn’t say that,” said Mr Butterly.

Mr O'Higgins later asked Mr Butterly: "Is there anything you would do differently?"

"The only thing: I would have never have gotten involved in converting that factory into a nightclub," Mr Butterly told the inquest.

New evidence